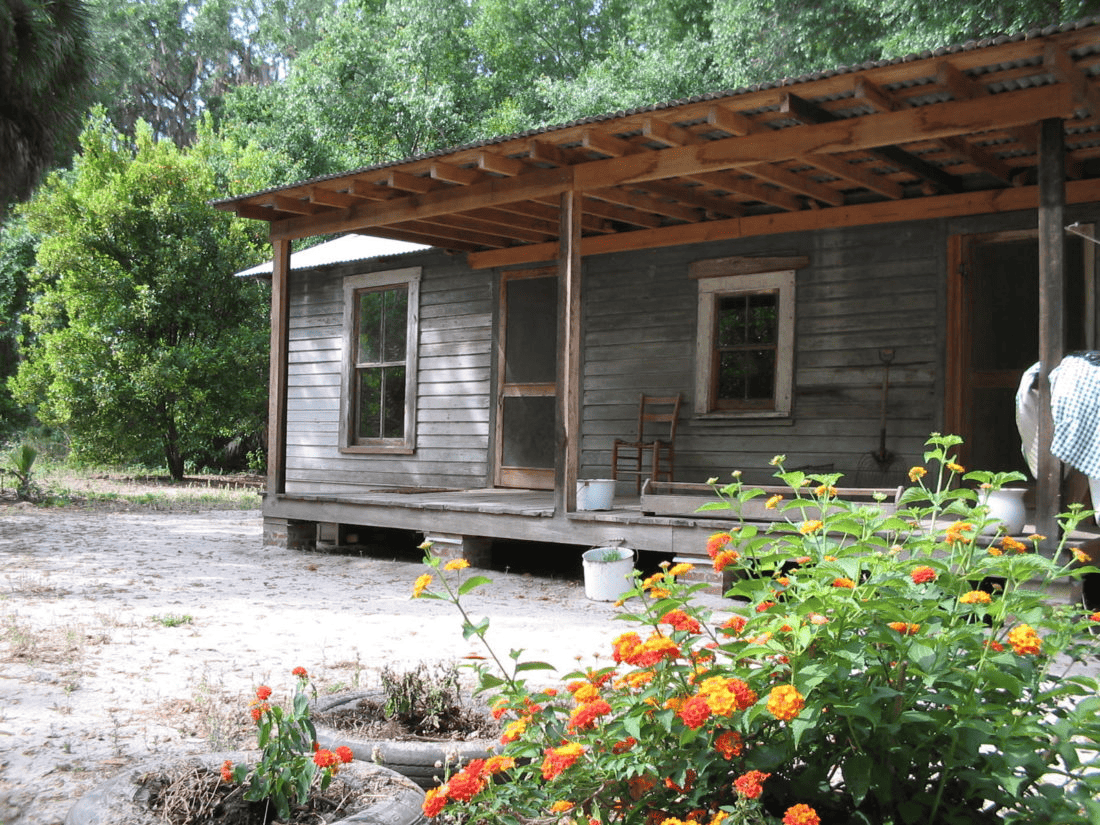

So, I went off trying to educate myself about racism, and I discovered a new garden style. Funny how these things happen. They are rapidly disappearing, but the African American-swept gardens (or yards) of the Southern USA are worth studying.

Have you heard of a ‘swept yard’?

My education so far has largely come from this interesting 1993 article about Georgia’s African American Swept gardens by Anne Raver in NYT.

Over 25 years ago, she called them a dying tradition of the American South. I can only imagine what has been lost or forgotten since.

A swept yard is a lawn-free style of front garden that has its roots in West Africa. The ideas made their way to the American South due to the slave trade. They were maintained to be weed and debris free with handmade stick brooms.

The yard was also the heart of the home since the inside quarters were not cooled and much of the work of living took place outside.

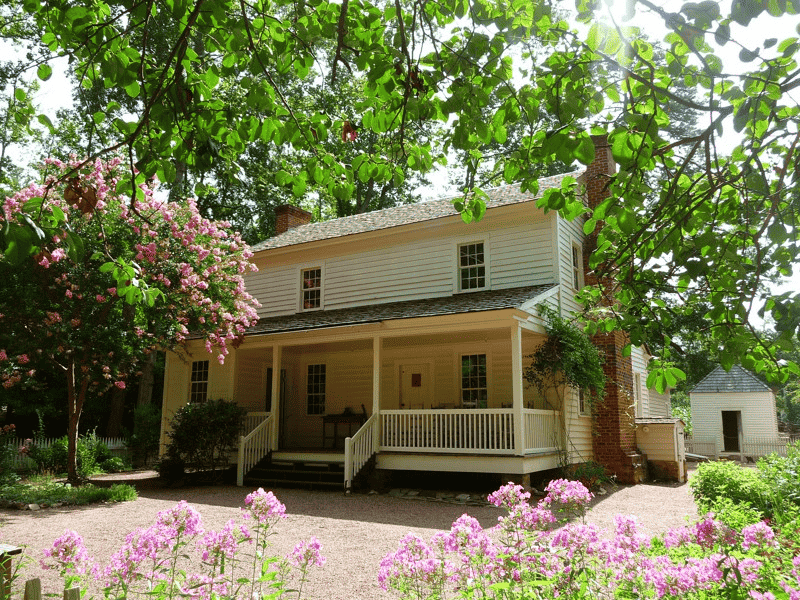

If you live in the south – it is worth studying how all people throughout the history of the region have responded to the conditions of the landscape and used their culture and skills to transform their outdoor spaces. While it is nice to recommend the typical plants of many modern landscapes for places like South Carolina and other southern states- it is also important to recognize that the majority of typical modern garden style is born primarily of white colonial slave owners and their European cultural roots and ideals. Learning to value and incorporate native plants as well as the wisdom of a variety of people who adapted the landscapes they lived in will better inform your design decisions and options.

Southern Slaves and Lawn Free Yards

The idea of a lawn-free front garden isn’t the exclusive domain of water-worried, environmentally minded modern gardeners. It was originally the very practical design of African American slaves in the South. And as you can imagine, there are some very compelling reasons why these gardens can and should inspire us today.

Grass often causes more problems than it solves.

Mowing, maintenance, and chemical dependence are all monetarily and environmentally expensive side effects of not seeing the beauty or function of a clean patch of dirt. Being able to afford the perfectly manicured ground covering of grass remains a powerful status symbol that we Americans cling to. I’m guessing that part of our cultural obsession with lawns is a remnant of status markings that have always placed English and European indications over African. And it persists today – white people’s neighborhoods are still wall-to-wall lawns… non-white neighborhoods – less so.

Grass conveys status.

Like it or not, it says “I have the time and money to keep this swath of green in perfect shape – I have means – I am better than anyone that can’t keep it perfectly green”. And we collectively buy into it.

I hear it from design students and clients all the time: Coveting of a neighbor’s perfect lawn. Lamenting our less-than-perfect. It is such a dumb social construct I simultaneously want to laugh at its absurdity and scream at its stupidity. (Seriously, we rank and compete on lawns??!!).

When you think about what you want people to think about you when they see your house (or any other outward expression of your taste and style) – what is the message you intend to send? Take a minute to think about the top three things you want your look to say about you. (Whether in fashion or garden design or anything else).

What are they? My list is this – I am interesting, I am clean and healthy and approachable, and I am unique. What is yours? Does it include “I’m rich” or at least “I have substantial amounts of disposable income”? If not, maybe you don’t need to be so concerned with your lawn.

Lines tell us what to do.

Paths are lines that show us where to go. Other lines can draw our eyes and lead us to see things in certain ways. Lines have superpowers in design, and it’s striking there aren’t very many lines in these types of gardens. A lack of lines and clearly defined spaces indicates that maybe the whole space didn’t have a singular use. Rather, it was open to lots of options.

Historically, this is, in fact, the case. These gardens doubled as workspaces, social spaces, play places, cooking and cleaning spots, and dining places. It’s a good reminder that the more hard-working or malleable you want your garden to be for different uses, the more strategic and picky you need to be with your lines.

Practically speaking – no grass also means fewer snakes and fewer fire hazards.

A clean dirt moat allowed residents to see if a venomous snake had infiltrated their barrier because its tracks were clearly visible.

The wooden houses that swept gardens surrounded were literal tinderboxes. As climate change intensifies and more and more of our modern homes are threatened with the fires caused by drought… the dirt moat isn’t such a bad idea.

The plants that graced these gardens were functional and without aesthetic order.

Instead, it was always about where it would work and survive and where it would be useful. Dr. Lydia Mihelic Pulsipher, a professor of geography at the University of Tennessee who has studied slave gardens in the Caribbean, which blend African and West Indian traditions, explains: “…plants have lots of different uses, and a lot of where they’re put is practical.

The West Indians plant an herb they call the pot scrubber bush — it’s in the daisy family, and it has a very abrasive leaf — wherever they clean up the kitchen stuff, which is usually under a tree in the yard.” (quote from Anne Raver’s NYT article above) It is helpful sometimes when trying to contemplate the design of a garden to focus on function first. Aesthetics can often be layered in or augmented as you refine a design.

African American Swept gardens were not expensive

Last but not least – these gardens were not cheap. They made do with found and recycled materials. There is an increasing need for all of us to examine each thing we consume and evaluate its value based on sustainability. Of course, this wasn’t the original terminology used, but don’t forget that necessity is the mother of invention and that oftentimes, junk can be recycled into something beautiful and useful.

Plants that Punctuate

Ok- one more thing… African American swept gardens were often punctuated with singular colorful plants like a pot of geraniums. While I am a huge advocate for repeating, and I tell my garden design students to repeat, repeat, repeat (and then I repeat that again as my design mantra) – I can’t argue that sometimes a singular, stunning plant can be a focal point that provides a place for your eye to start when taking in all the other details. And also, bright pops of color always evoke a playfulness and a sense that we aren’t taking this all too seriously.

I posted a charming before and after of a swept garden in Georgia over on my instagram today . I have to say, I don’t hate the before – the big opuntia cactii might have been a little overbearing but I also think the lines that point visitors to the front door are very modernizing. Take a look and let me know what you think of this updated ‘Swept Yard’ in the comments.

I’m guessing the swept dirt yard had an additional benefit of seeing human tracks, a kind of old school surveillance. I’ve also seen this idea in Mexico, where sand has been dominant. Something about the human touch, I suppose, makes it gardening.