The Disruptor series started in the print pages of P+V. The first interview was with David Milarch, who is saving and restoring old-growth forests and champion trees through cloning. Meeting and talking to people who I admire and who inspire the kind of work I value serves many purposes. It helps me to continue to thrive. I need to hear their stories, see their struggles, and learn about how they did ‘it’ – whatever’ it’ is.

I also hope it helps to cheer them on, and I hope it inspires you. Fellow garden writer Debra Prinzing has started a movement and a nationwide conversation around local and American-grown flowers that has changed the way we purchase cut flowers.

This interview shares some of her ‘Slow Flower’ story. My personal favorite part is how this remarkable movement, which has spawned multiple books, embraced and supported thousands of small farmers (most of which are women), and has even seen Debra lobbying Congress, was originally born of a blog series. For a blogger like myself, it doesn’t get any more interesting and exciting than that.

Debra Prinzing, Can you tell us about your background?

I’ve been in and around the garden writing world for two decades, ever since I quit my business reporter job in 1998 after my second child was born. At the time, I wanted to pivot to features writing, particularly home and garden and lifestyle topics.

Miraculously, I mentioned this idea over coffee to a professional contact, a friend who ran one of the only woman-owned advertising agencies in Seattle. And she told me she’d just signed on a new independent nursery to do its media buys.

She made that introduction, and I reached out to the GM whom I met with about possibly doing some writing for their nursery. It didn’t pan out, but a month later, that GM called me and asked, “Do you do newsletters?”

That connection was my wonderful door-opener, and I ended up freelancing for that nursery, Emery’s Garden, in Lynnwood, Washington, for four years.

The crash-course in horticulture couldn’t also have happened without my taking dozens of classes at South Seattle Community College’s landscape horticulture program, immersing myself in the subject. I soon became the Northwest Horticultural Society’s newsletter editor, and with my newspaper background, I landed regular gigs with several Seattle area dailies, including a weekly design column in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, a Hearst publication.

I wrote a number of books and continued to “trade up,” as they say, with more reputable or sizeable publications, both magazines and newspapers.

How did you evolve from garden writing into writing about floral design and then the floral industry?

During that period of time, I dabbled in writing about floral design, especially for Romantic Homes magazine, which had a standing feature called “Blooms,” which involved the art director sending me a set of film from a photo shoot and asking me to call a florist, usually someone in LA, to extract the narrative. I remember being so surprised that I knew more about the actual botanical ingredients used in those photographs than most of the florists I interviewed.

In 2006, I met a young flower farmer named Erin Benzakein, who was growing sweet peas and having babies. She was so passionate about trying to break into a closed floral industry here in the Pacific Northwest, one that didn’t value local or organic flowers but still based business on price alone.

With my business reporting background, I saw a big story — one that was not pretty, actually. One in which small, sustainable farms could not compete successfully on an “uneven playing field” where imports could undercut prices.

I learned through Erin and later through my friend Amy Stewart’s wonderful book Flower Confidential (published in 2007) that preferential trade policies, low wages, and lax environmental regulations benefitted growers in South America and hurt domestic flower farms.

That inspired me to tell a different story, to pick up where Amy’s book left off and show readers – gardeners, really, who were my audience – a better way to be beautiful.

As you started to take up the cause of local flower farmers, what were your first steps?

I partnered with Seattle photographer David Perry, the man who originally introduced me to Erin, and we developed the idea for a book, a documentary-style project that told the stories of the emerging renaissance in America’s cut flower farming and floral design industry.

David and I self-financed the creation of The 50 Mile Bouquet, determined to even self-publish if we couldn’t interest a publisher. It took about five years of picking up and setting aside, then picking up again the vision we had for a book. Wherever one of us traveled, we tried to meet American flower farmers and their customers, impassioned florists who also cared about the origins of the stems and petals they used.

By 2011, our book was already being designed by art director James Forkner when we met Paul Kelly of St. Lynn’s Press. Paul picked up the book’s production and distribution, and The 50 Mile Bouquet (T50MB) was published in the spring of 2012.

By then, I had also started a personal project called “Slow Flowers,” which I thought might become a blog series. I challenged myself to create one bouquet each week throughout a 12-month calendar year.

The project was my response to a former NY editor of mine who had rejected T50MB, saying, “local flowers are fine if you live in a place like Santa Barbara, but they’re not relevant to the rest of the country.”

Told that my idea was “fringe” and not sellable, I set out to prove that editor wrong. It stimulated me to harvest botanical ingredients from my Seattle backyard and augment them with flowers, foliage, branches, and flowering bulbs purchased from local flower farmers.

How did Slow Flowers go from being a blog series to a book and then a nationwide movement?

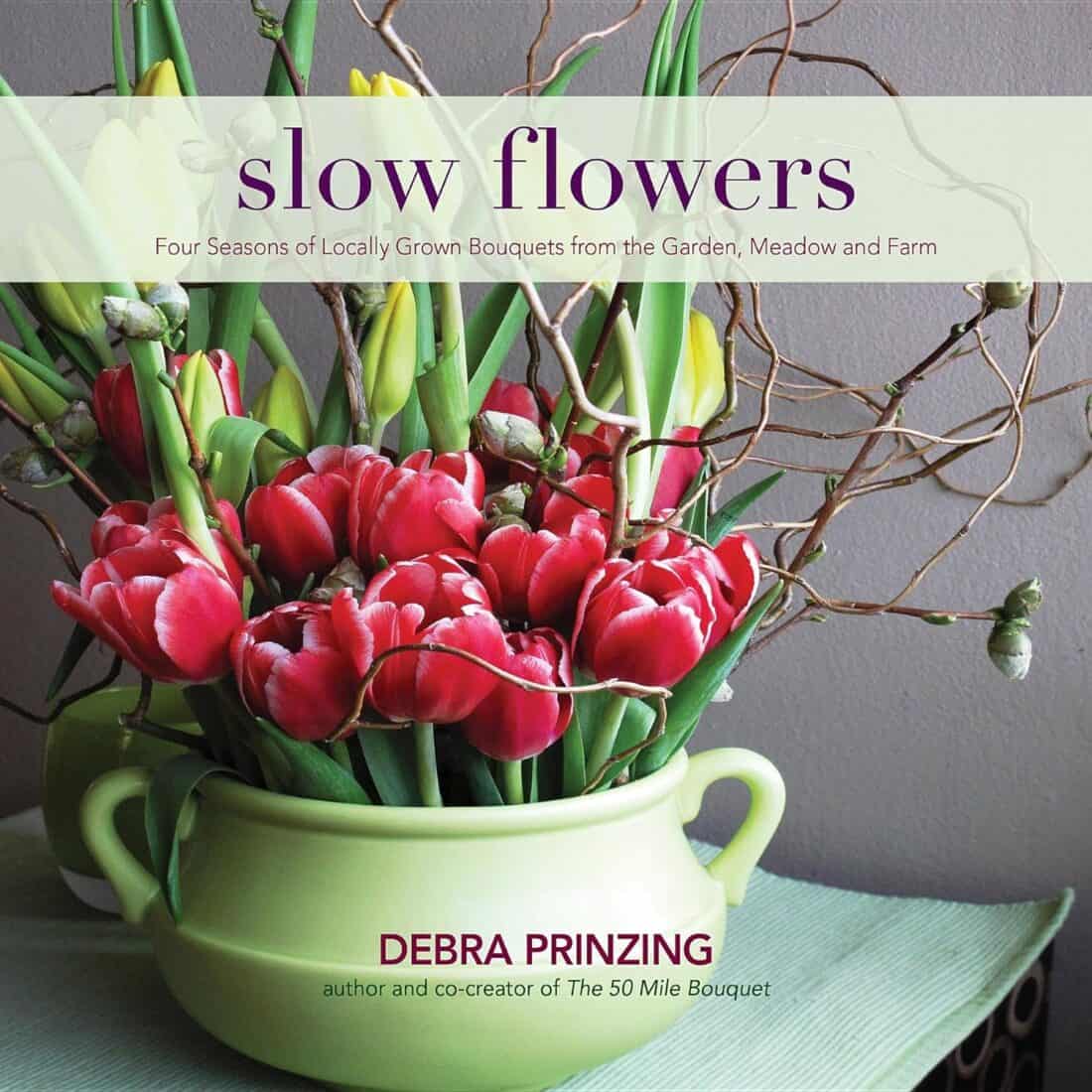

Slow Flowers, the book, was published one year after T50MB, in spring 2013. As I led workshops, gave lectures, and spoke with bloggers and writers about the idea of living seasonally with flowers the way a chef lives seasonally with her or his menu ingredients, I was often asked: “How do I find flowers that I know are local? How do I find farmers and florists who supply them?

In my responses, which were often unsatisfactory for people in certain parts of the country, I often told myself that “someone should start a directory of American-grown flowers.” That notion wasn’t so alien to me, as I had worked with Amy Stewart and a few other colleagues to launch Great Garden Speakers, a directory of sorts, which we launched in 2011. I understood the database platform on which GGS was built, so I knew there were tools out there to work with.

So that “someone” became me.

It took nearly one year of development to launch, and we unveiled Slowflowers.com in 2014, just before Mother’s Day. Slowflowers.com was funded with about $12,000 of my own money from a liquidated IRA, and when it became clear that the amount wouldn’t cover our launch, I turned to Indiegogo with a campaign to raise another $12,000. The campaign blew my mind. It raised more than $18,000 from 229 backers, giving us the funds to finish the phase one development and get Slowflowers.com launched.

In conjunction with the Slow Flowers book, Slowflowers.com, and our popular “Slow Flowers Podcast with Debra Prinzing” (launched July 23, 2013), my life has turned more passionately to flowers. I kind of fell down that rabbit hole, and I often ask myself, ” – Why?

I regularly ask myself why I am where I am – I am fascinated by the insight I can only see by looking back. Why do you think you evolved to this place?

I was by all accounts a moderately successful “garden writer,” with bylines in the Los Angeles Times, Metropolitan Home, Garden Design, Better Homes & Gardens, and many other titles. But I felt like a generalist.

I wrote about design (architecture and interiors) as a specialty in addition to gardening, which is something very few of my peers could do. I delved into architecture even deeper in 2008 with Clarkson Potter’s publication of my award-winning book Stylish Sheds and Elegant Hideaways (with photographer William Wright). But somehow, the traction I had hoped to achieve with a sequel to the shed book, with endorsements or co-branding opportunities in the “outdoor living” space, never happened.

I was really ready to go big and attach my name to something that mattered… and when I embraced American-grown flowers, those flowers embraced me. The people in this industry (flower farmers, floral designers, and farmer-florists) embraced me and saw me as their informal spokesperson.

It has been super rewarding. I haven’t turned my back on those wonderful publications I name above; in fact, several of them are still on my current list of writing outlets, especially Country Gardens, where editor-in-chief James Baggett encourages me to produce flower farming and floral design stories whenever I can.

What is Slow Flowers now?

The Slow Flowers Movement plays an important role in giving American flowers a voice — connecting flower farmers with florists and their customers, anyone who wants to signify or commemorate a life event, or just have beauty and nature in their lives.

By convening the conversation and elevating the story of “rock star flower farmers” I have given farmers a narrative, encouraged them to find their own unique stories, and to differentiate their flowers from commodity crops that are basically dumped on the US marketplace.

Much like the Slow Food Movement became the anti-fast-food cause, Slow Flowers is the anti-imported-flowers cause. This has happened at a time when Americans are asking about the origins of their purchases in all consumer categories; they are concerned about saving US jobs, preserving farmland, about stimulating economic development in urban, suburban, and rural areas alike.

When you know the farmer and her or his story, you have a different relationship with that bouquet in your hands or vase.

And if you can make one small gesture to buy American-grown and local flowers, then you feel empowered to direct the course of an entire industry.

Certainly, we are not going to eliminate imports, just as we can’t eliminate imported cars or imported fashion. Too many agricultural and manufacturing operations have been sent overseas, damaging our infrastructure. But there is an opportunity to differentiate in the crowded floral marketplace, and Slow Flowers is giving progressive farmers and florists a new way to break through that clutter and be a better choice.

This series started as I looked around and wanted to talk to and talk about creative people who aren’t big tech or typical ‘Shark Tank’ material but who are creating movements and businesses that matter. I think the term ‘disruptor’ describes you perfectly, and I wonder if you see yourself that way, too, and why?

I simply can’t accept that we Americans are spending millions, if not billions, of dollars, buying a perishable product that is grown far away and is shipped to us on jumbo jets using quantities of fuel that defy the imagination. As gardeners, especially, and that is my point of view, it makes no sense.

I believe floral consumers who are gardeners are driving this movement with their pocketbooks and practices. They know how flowers grow; they know the seasons, the bloom cycle, and the benefits of having plants in our lives.

So they “get” it, and when I can connect the dots with my articles, lectures, podcast episodes, and outreach campaigns like American Flowers Week, then there’s a newfound embrace of this movement. People are looking at labels, they’re shopping at the farmers’ markets, they’re asking florists to use only local flowers in weddings or events. They are searching for meaning and connection for their purchases.

I am able to disrupt because I am an outsider; I don’t adhere to the “rules” that exist in mainstream floristry. I am self-taught as a designer, and I am able to say that the “emperor has no clothes” when others are afraid to.

If I can suggest alternatives to conventional florists who feel boxed in by Pinterest or Martha Stewart or their hometown wholesaler who only imports from South America because it’s more “convenient,” then I want to play that role.

Ultimately, consumer preference will shift the marketplace. If that means each grocery store and wholesale florist in the country adds a “local” or “American-grown” floral section, then I’ll be happy. It’s choice that matters. And until I started asking the question about flower sourcing, there was little or no desire to offer choice.

What is next?

In 2016, American Flowers Week, which was launched in 2015, grew to include participation at all levels of the floral distribution channel – from farms to wholesalers to online sellers to grocery, with 1.3 million impressions, tripling the first year’s participation.

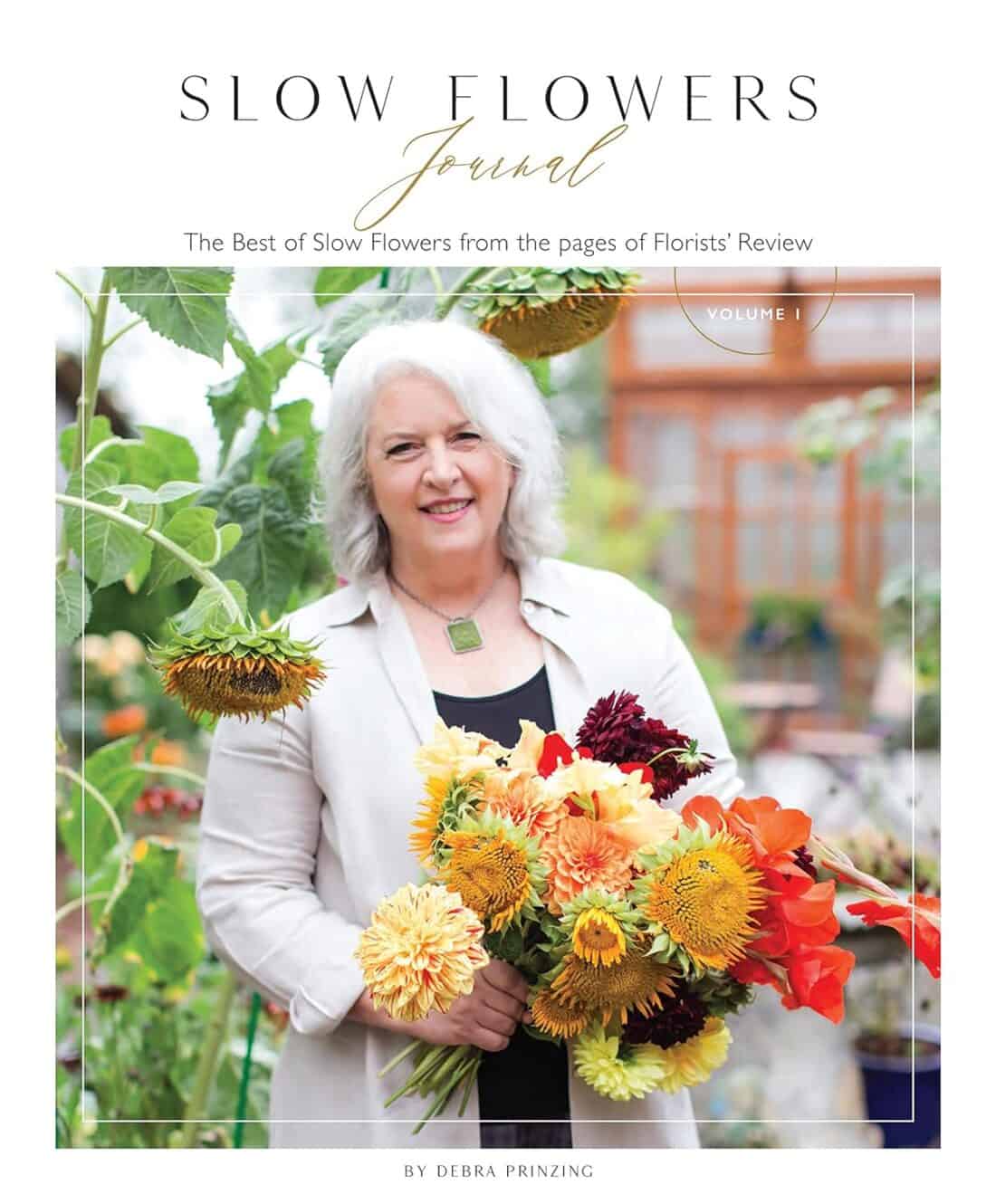

Slowflowers.com also expanded to include 700 participating members, and the Slow Flowers Podcast reached 100,000 listener downloads. Going forward, I have plans to introduce the Slow Flowers Journal, an online design magazine featuring stories of the people, places and flowers in the Slow Flowers movement.

Read more about Debra Prinzing and Slow Flowers.

Similar Posts:

Wonderful story about someone I admire so much!

Linda, – I am glad you like it – I got a lot out of it as well. I very much admire her, her ability to pivot, drive a project (actually lots of projects – and while also being a mom!) and make things happen too!

What an inspiration and true leader! Thanks Debra!

I have known Debra since collaborating with her in 2004 on floral arrangements for an article in Romantic Homes. More recently I have worked with her as a board member for the Seattle Wholesale Growers Market; a co-op of local flower farmers that she helped to shepherd into existence. Her work is truly changing the floral industry; I think for the better. Bravo Debra!