After ten years of staring down a large pile of hardwood logs left for me after the installation of a new home septic system, I’ve resolved to make something of this eyesore. Can I figure out how to design and grow mushrooms outdoors in a forest garden? Is there such a thing as garden design for mushroom gardens?

I’m a classically trained garden designer. (That is to say, I studied in England and among many more useful things, I learned from the best about how to design 20-foot-deep herbaceous borders and other stuff most normal people don’t really want).

English Garden Design Training vs Syntropic & Permaculture Farming

Running contrary to my formal training, notions of hügelkultur* and permaculture fascinate me as I try to manage my own three-acre garden.

Syntropic and permaculture farming practices are two approaches to garden-making that couldn’t be more different from a traditional English approach.

I find my biggest struggle in marrying the mindsets is resolving the part about aesthetics. One is all about making things pretty in the most planned, pruned, and primped of ways. The other relies on seeing beauty in something that most would call a weedy, chaotic mess.

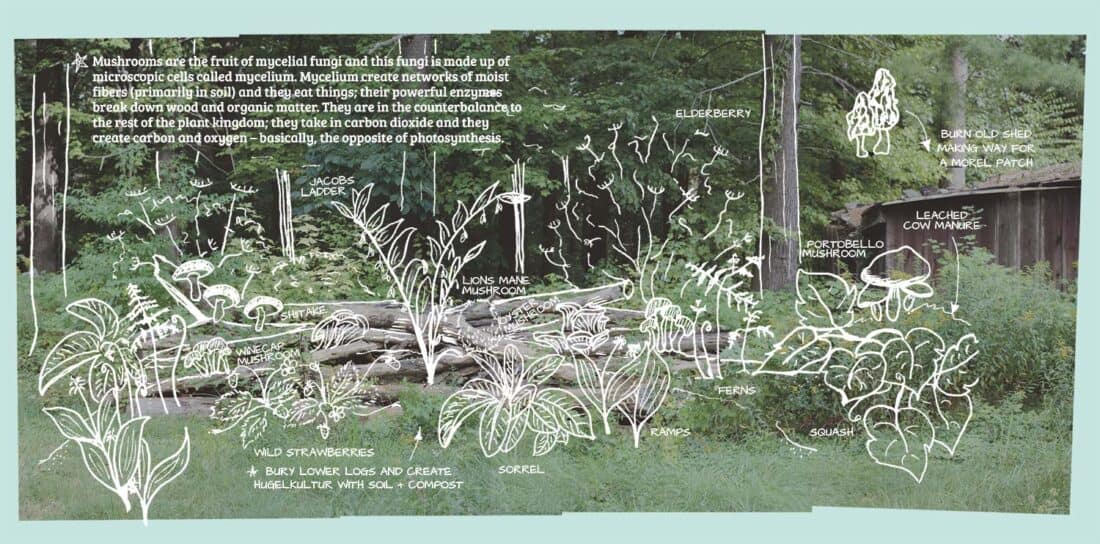

So, as I make plans for my pile of rotting logs, I’ve set a goal of experimenting with mushrooms and perennial vegetables. I want to loosen my grip (a little) on what it will look like and let wilder forces take hold.

I want to create an edible food forest garden and gourmand’s delight while trying out plants and methods that should do the hard work for me and the ecosystem. But (here is the tricky part) I want to figure out a way to make it look like something I would proudly share as an attractive example of garden design.

Can it be done?

Let the experiments begin.

How to Grow Mushrooms Outside – Growing Mushrooms on A Log Pile

If gardening is about wrestling around with Mother Nature to sculpt something of self-perceived beauty while absorbing her sometimes gut-busting blows with grace and patience, then it seems to me that beautiful mushroom cultivation might be like entering an ultimate fighting championship.

Not surprisingly, I have had to deal with a couple of sucker punches to my initial plans.

First, my old pile of logs isn’t actually the mushroom-growing haven I thought it would be. And second, mushrooms don’t grow where you plant them (so much for my ideas about color-coordinating companion plants).

It turns out my old logs are pretty useless to most mycelium. In general, mushrooms want fresher, more nutrient-rich wood. But, I am undeterred and have instead decided that the existing logs will largely form the base of the hügelkultur*.

How to Plant an Edible Food Forest Garden

The other half of the property is woodlands. We have plenty of newly fallen trees and a constant supply of garden clippings we can impregnate with mushroom spores. The strategy is to bury the bottom half (at least) of the logs with soil. This will create a base growing medium for other foodie treats like ramps, ferns (for fiddleheads), Solomon’s seal (harvest young shoots in early spring, prepare and eat like asparagus), elderberries (I can’t wait to make home-brewed cordial), sorrel and wild strawberries. The top area will be filled with pockets of sawdust, coffee grounds, compost, and other growing medium for a variety of mushrooms.

There is a third harsh reality of my experiment. This will take time. Not only will the mushrooms potentially run and grow not where I spread or inoculated with spore, but where I least expect. It might take months, even years, before they bloom. The rest of the time, I have to trust that they are growing and spreading via vast underground mycelial networks—invisible to my naked eye.

The general faith of a gardener is legendary, but this is pushing even my limits.

* Hügelkultur is a composting process employing raised planting beds constructed on top of decaying wood debris and other compostable biomass plant materials. The process helps to improve soil fertility, water retention, and soil warming, thus benefiting plants grown on or near such mounds. (Wikipedia)

Choosing edible forest perennials to grow in your mushroom garden:

Mushrooms come in all shapes, sizes, and even colors – but they aren’t a lot to look at. As I consider how to start a mushroom garden, I realize like any other garden, i need to consider companion planting. Making a lush and interesting landscape full of other edible woodland plants in my home garden will round out the collection but also give other exciting edibles.

My companion planting choices for an edible food forest and mushroom garden

Allium tricoccum – Ramps, wild leeks

Ramps are native to moist wooded areas. People like them because they are a delicate blend of onions and garlic that you can even eat raw.

Start with seeds – a colony will gradually form over a few years. Less patient garden makers can also find bulbs (in season) to get a jump on production.

Ferns – Choose a variety that works where you live.

Athyrium filix-femina – Lady fern, Osmunda regalis – Royal fern, Polystichum munitum – Western sword fern, and Osmunda cinnamomea – Cinnamon ferns are what I am considering.

These ferns are all sources for tasty fiddleheads in the spring and will provide lush foliage in the summer and fall. A few already grow here, so I can transplant them from my woods to get things started.

Fragaria viginiana or vesca – Wild strawberries

Due to their short lifespan after picking, these strawberries are rare in markets. Wild strawberries are more flavorful than commercially cultivated varieties, so the best place to get them is from your own garden. The fruits are much smaller, and the plants can be a great groundcover.

Rumex acetosa – Garden sorrel

The leaves of perennial sorrel are refreshing and lemony. Add them to soups and salads. Also, the juice of the plant removes stains from linen and natural fibers (bonus!).

These also grow where I live, so planting some from seed will be easy. I find their russet brown seed heads very attractive and an interesting contrast to an otherwise green group of plants.

Polygonatum ssp – Solomon’s seal

Varieties can range in height from 8 inches to 4 feet. Solomons’ seal is grown for its beautiful arching stems, textural leaves, and herbal qualities. Polygonatum’s leaf coloring can range from silver to green and also includes variegated varieties.

Sambucus nigra ‘Black Lace’

Not only a source of harvestable flowers, the ‘Black Lace’ variety will also give depth and color with its dark purple leaves. The fruits are also edible but only after cooking, and they are often made into jams.

How to Grow Edible Mushrooms outside in the forest garden:

Growing mushrooms at home with indoor kits is a popular way to experiment with cultivating fungi. But I’m not into moldy logs in my living room.

Plenty of mushrooms grow in my garden already and some of them I know to be edible. I regularly get morels in my front beds and between the stones of my front walk. The plethora of naturally occurring mushrooms leads me to think that starting a mushroom garden outside (on purpose) is an entirely reasonable goal. Plus, a walk in the forests all around where I live constantly serves up a plethora of fantastic mushrooms.

If you are going to try growing mushrooms at home, make sure you know what you have growing naturally. Basic mushroom identification courses are readily available through extension programs, botanic gardens, and mushroom hunting groups.

Lentinula edodes – Shiitake

Shitake prefer the dead or dying wood of broadleaf trees. It is best to use logs that haven’t made ground contact as native soil microbes can compete with shiitake mycelium. Alternatively, shiitake mycelium can be grown on bags filled with fresh sawdust.

Stropharia rugoso-annulata – Wine cap mushrooms

Native to New England, wine caps can be massive (up to 5 pounds). They are typically found growing on old compost heaps in a shady area. Truly magical, they often look like rocks, are cold and firm to the touch, and they can grow fast. They can sometimes reach full maturity and size between dawn and dusk. Inoculate newly disturbed soils rich in wood debris by making a moth patch—a lens-shaped patch of woodchips.

Pleurotus ostreatus – Oyster mushrooms

These are the most common edible mushrooms found on hardwoods. Grow on logs and stumps of alder, cottonwood, poplar, oak, birch, beech, and aspen, among others. After incubating, the logs may be partially buried horizontally to conserve water during fruiting. Spent oyster kits are a mass of sticky white mycelium typically grown in straw or wheat. I am adding these remains to my mushroom garden. You can use them to inoculate a compost heap or stuff into cracks between pieces of wood (adding sawdust, coffee grounds, and straw to help feed and maintain moisture).

Agaricus bisporus – Portobello mushrooms

Portobellos grow in mounds of inoculated leached cow manure or compost. Use cover crops to promote growth. Portobellos like to grow with other plants. Pair with kale, zucchini, squash, potatoes, melons, or similar leafy green vegetables.

Morchella angusticeps – Black morels

Morels are common mushrooms to hunt for because they can be a bit tricky to cultivate. Grain spawn—a sterile culture grown on grains—grows on leached cow manure. Morels are also grown in burn areas because they tend to colonize ground that has been charred.

Hericium erinaceus – Lions mane mushrooms

Lions mane mushrooms taste like shrimp or lobster when cooked. These mushrooms are pure white until aged. When they begin to turn brown at the top is the perfect time to harvest. They prefer the wood of dying or dead oak, beech, or maple trees. To cultivate, use 4-foot inoculated logs buried in the ground.

Related how to grow mushrooms outside and edible forest garden posts:

Photo Credits:

Ramps – Charles Kinsley (CC by-SA 2.0), Strawberries – Alexander Vasin (CC by 2.0), Polygonatum – Blueridgekitties (CC by-NC-SA 2.0), Fern – Alison Nihart (CC by-SA 2.0), Rumex Acetosa courtesy of Edible Landscaping, Sambucus nigra ‘Black Lace’ – Courtesy of Proven Winners

Mushrooms: All images via 123rf.com with the exception of Wine caps – Ann F. Berger (CC by SA-3.0), Portobello – Ron Pastorino – (CC by SA-3.0)

Share this Story:

+comments+