As gardeners and garden designers, we understand the nuanced sense of place that is coded in each handful of soil. The land on which we toil is as unique as our fingerprints, and it can make our plants and gardens grow in highly regionalized ways. A pink flower in one garden can be very different in another. Similarly, a vegetable’s nutritional value can be more or less based on the terroir of the place where they are grown.

TERROIR: THE SET OF ALL ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS THAT AFFECT A CROP’S QUALITIES, INCLUDING EVERYTHING IN ITS HABITAT.

There are many layers and elements that make up the underground world, and it is a place we often fail to consider. The subterranean landscape is as wild and even more unknown than the one we see above ground. This guide will break down all the pieces and parts that make up healthy soil.

Rain Water

Raindrops have a huge impact on the surface of the earth. When they hit bare soil, they cause runoff, which displaces soil particles on the surface. Rain also compacts the soil and causes erosion and leaching (all of which are a waste of valuable resources). Vegetation, mulch, and leaf litter prevent excessive runoff and help the rain enter the root zone where plants can benefit from it.

Recent research has shown that the petrichor (the earthy smell of rain) we smell after a rain shower is actually the release of chemicals on the surface of soil into the air. This is leading to further research on how rain can spread soil-borne microbes or pesticides.

Mycorrhizal Fungi

A mycorrhiza is a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and the roots of a plant. The fungus colonizes the plant’s roots, but rather than hurting the plant, it helps with things like absorption. Most plants (approximately 95 percent) have the ability to form mycorrhizal relationships. By doing so the mycorrhizal mycelia (which are much smaller than plant roots) can extend farther in the soil. The mycelia also have different membranes that can allow nutrients to pass through them more easily. High levels of soluble phosphates (found in many fertilizers) in your soil will result in reduced root colonization by mycorrhizal fungi.

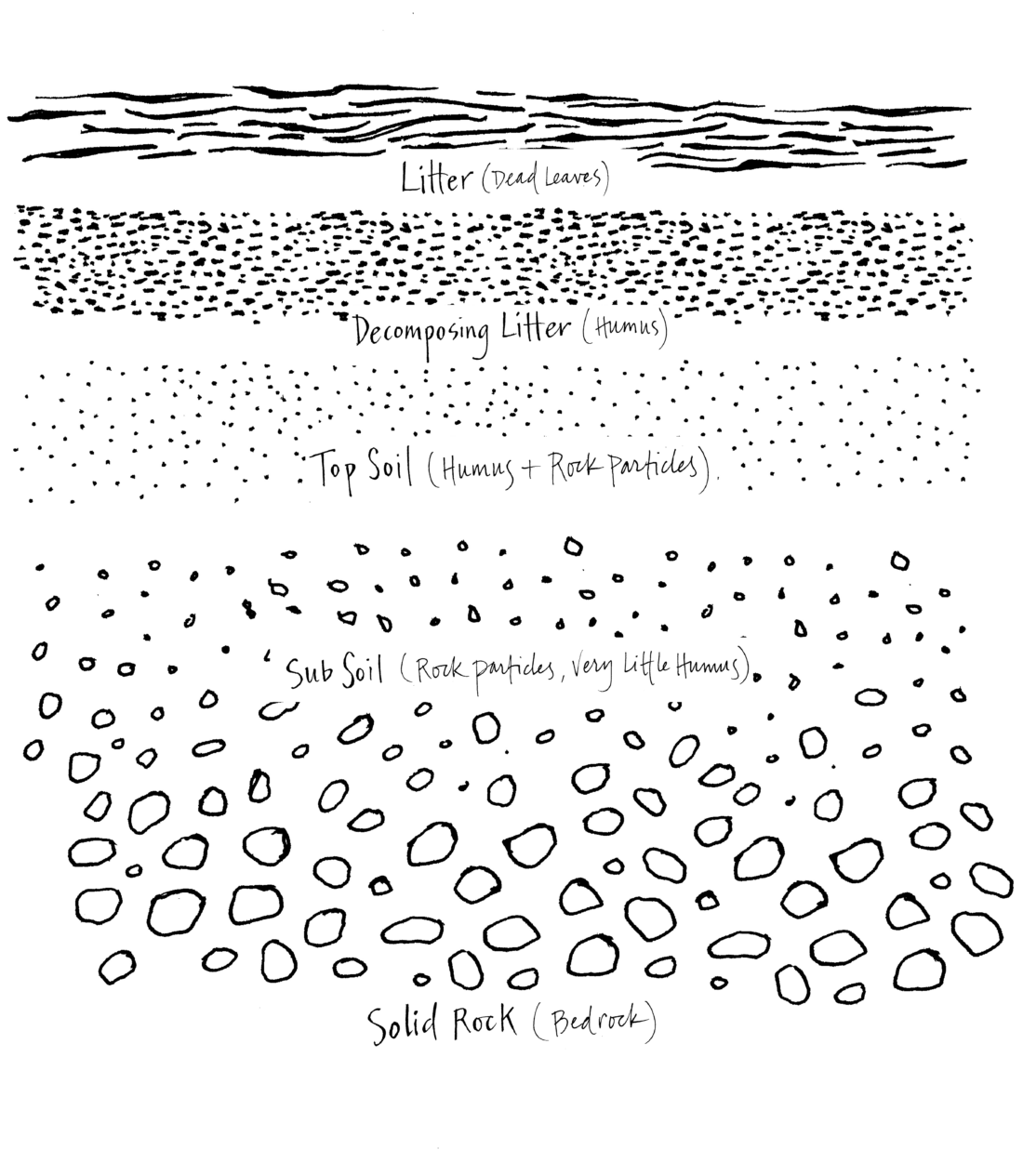

Litter (Dead Leaves)

Made up of dead plant material (leaves, twigs, seeds, bark, needles), litter is home to a myriad of tiny and microscopic creatures that use it for shelter and food. These creatures help decompose and spread the nutrients into lower layers. Litter varies depending on the season, elevation, latitude, climate, and ecosystem. It serves to protect lower soil layers from rain impact (which would otherwise cause hardening and a loss of porousness), wind erosion, and loss of moisture.

Saprophytic Fungi

Saprophytes are fungi that live on dead or decomposing plant or animal matter. They break this organic matter down into the humus, minerals, and nutrients directly utilized by plants. The fungi usually exist in a microscopic form, but occasionally, they may produce either an unusually prolific amount of growth or fruiting bodies (which we call mushrooms). At this point, they become noticeable to humans and may cause a few (usually transient) problems for the gardener.

Decomposing Litter (Humus)

Litter becomes humus through the process of humification. Humification happens in a compost pile (when we create them) or naturally when litter fully decomposes over time. Unlike compost, humus is fully decomposed and will not break down further. Humus is uniform and dark (a trait that helps to warm soils in the spring), inert, and lacks shape or structure. The process of getting organic matter converted into humus is what maintains a healthy population of soil microorganisms (earthworms, mites, bacteria, nematodes, and others). Humus stabilizes soil by binding with nutrients that plants need (as well as pollutants). It protects these nutrients from leaching out of the soil by water.

Top Soil

Topsoil is usually between 2-8 inches deep and is the outermost layer of soil. The buffer zone between lower rock layers and upper organic layers is where most of the biological activity of plants and subsoil organisms takes place. These layers are teeming with life. Just one small section of a forest floor can be home to several thousand species of mites.

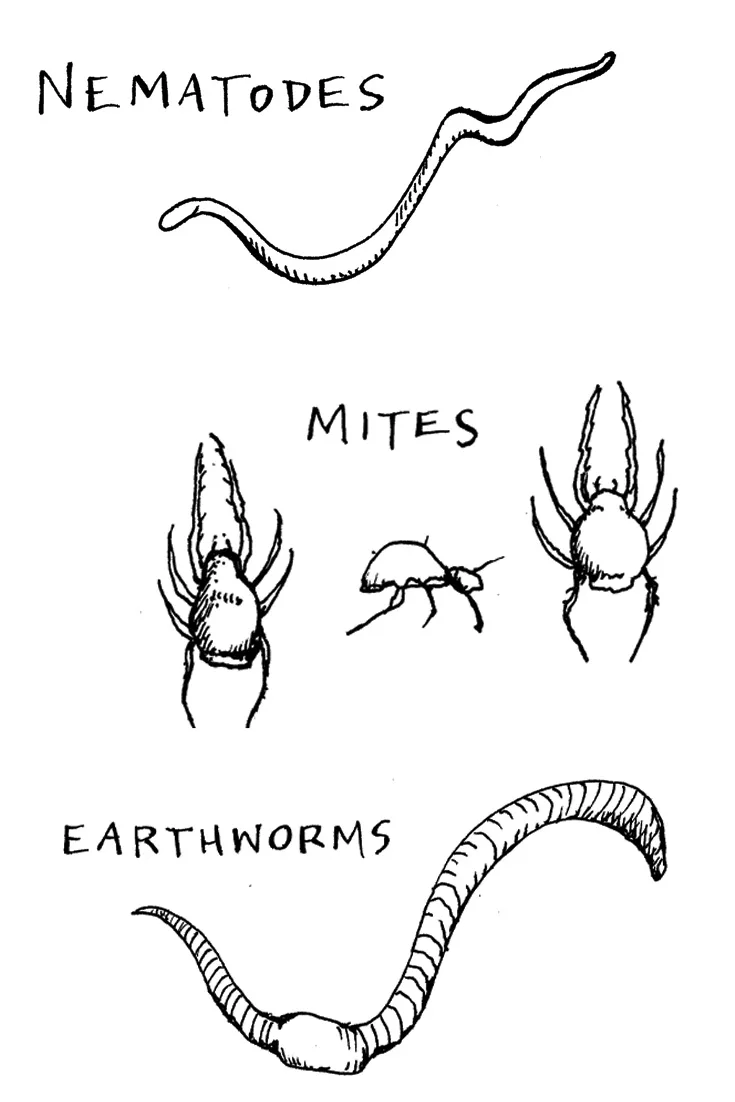

Nematodes

There are an estimated one million species of nematodes or roundworms. About half of them are parasitic and feed on a variety of materials like algae and fungi, fecal matter, dead organisms, small animals and living tissue.

Nematodes can be beneficial as well as detrimental to plants. The detrimental ones can spread plant viruses, while the predatory nematodes can be beneficial by attacking other garden pests and harmful bacteria. Nematodes are parasitic organisms that feed on living matter, thus aiding in decomposition. Their respiration plays an important factor in regulating the amount of Nitrogen that is available for plant uptake.

Earthworms

Earthworms play a major role in converting the dead organic matter that they feed on into humus. But they also act as biological pistons that force air (and oxygen) through the tunnels they create as they move. These tunnels help mix the soil as well as provide travel routes for other underground creatures who cannot push through the soil on their own. Earthworms are also at the base of many food chains and provide sustenance to a large number of insects, birds, reptiles, and mammals.

Regular use of nitrogen fertilizers will create acidic conditions in the soil that are fatal to earthworms. The best way to maintain earthworm populations is by adding organic mulch to the soil surface to maintain a food source.

Mites (Arachnid arthropods)

Many small arachnid arthropods (AKA mites) live in the soil, as do larger spiders; insects such as beetles and ants, as well as centipedes and even scorpions. In general, all of these arthropods can be classified as shredders, predators, herbivores, or fungal-feeders based on their functions in soil. Most soil-dwelling mites eat fungi, worms, or other arthropods.

These arthropods aerate and mix the soil, regulate the population size of other soil organisms, and shred organic material.

Oxygen

Plants are like people, and they need food, water, and oxygen to grow. The topsoil – where the oxygen is located – is where the biological activity happens. If soils become compacted, they will not allow water and oxygen to move, and there is also no room for roots to explore. At bedrock and subsoil levels, the oxygen level is too low to allow for decomposition.

Deep tilling can make matters worse by burying the organic materials normally found in top layers at a depth that causes them to rot. Shallow tilling, however, can incorporate more air at levels where oxygen can help speed decomposition. If topsoil is compacted, it probably does not have enough oxygen or water to sustain healthy plant life.

Ground Water

The addition of organic matter (manure or compost), especially humus, to soils, can improve the soil’s capacity to hold water. Soils with a high water-holding capacity can supply water over time when plants need it. As water is absorbed into the earth, and moves beyond the root zone, it becomes groundwater. Groundwater is the water that moves laterally and slowly towards the sea to complete the hydrological cycle, and it will also seep into springs, streams, rivers, and lakes on the way.

Minerals

In addition to carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, plants need at least 14 other minerals. The balance of minerals in the indigenous soil is responsible for the flavor and nutrition in edible plants and the terroir-specific characteristics of other plants, such as color, vigor, and scent.

A rose grown in one garden can be very different than the same kind of rose grown in another. The unique properties can be attributed to terroir.

Sub Soil

Subsoil resides beneath the topsoil and has comparatively little humus, organic matter, or, due to its depth, oxygen. It is made up of a mix of small particles but is mostly comprised of weathered stone (sand silt, clay). This layer is rich in minerals, and plant roots will weave their way underground to benefit from this wealth.

Solid rock (Bedrock)

Beneath the subsoil, bedrock provides the supplies for future soil. Even though it takes a long time to be exposed and weathered, the character of the bedrock directly affects the terroir of the soil. There are no organic materials or nutrients this deep, but the varied composition of the rock, along with the flow of groundwater (which transports and modifies it) defines the types of soil found in any particular region.

More about Healthy Soil Life and Soils for Gardening:

If you’re interested in learning more about soil – you might want to consider listening in on our Garden Makers Lecture Series talk with Dale Strickler (see below). Three times per year, PITH + VIGOR hosts talks with experts in the landscape and horticulture realm. Dale’s talk will help you not only further understand soil but how to manage it so you can grow more effectively and sustainably.

Other Soil Related Posts you might be interested in:

illustrations by Samantha Dion Baker

+comments+